By Rokeshia Renné Ashley, Florida International University

In “BLACK EFFECT," a track from Beyoncé and Jay-Z's 2018 collaborative album “EVERYTHING IS LOVE," Beyoncé describes a quintessential Black female form:

Stunt with your curls, your lips, Sarah Baartman hips Gotta hop into my jeans like I hop into my whip, yeah

The celebration of Sarah Baartman's features marks a departure from her historical image.

Saartjie “Sarah" Baartman was an African woman who, in the early 1800s, was something of an international sensation of objectification. She was paraded around Europe, where spectators jeered at her large buttocks.

With celebrities like Beyoncé recognizing Baartman's contributions to the ideal Black female body – and with the curvaceous posteriors of Black women lauded on TV and celebrated on social media – I wanted to understand how this ideal is viewed by the very people it most directly effects: Black women.

So I interviewed 30 Black women from various cities in South Africa and the mid-Atlantic U.S. and asked them about Baartman. Would her image represent a reviled past or a canvas of resilience? Were they proud to bear a similar buttocks or ashamed to share a similar stature?

Hips and history

Baartman, a Khoisan woman from South Africa, left her native land in the early 1800s for Europe; it's unclear whether she went willingly or was forced to do so. Showmen exhibited her throughout Europe, where, in an embarrassing and dehumanizing spectacle, she was forced to sing and dance before crowds of white onlookers.

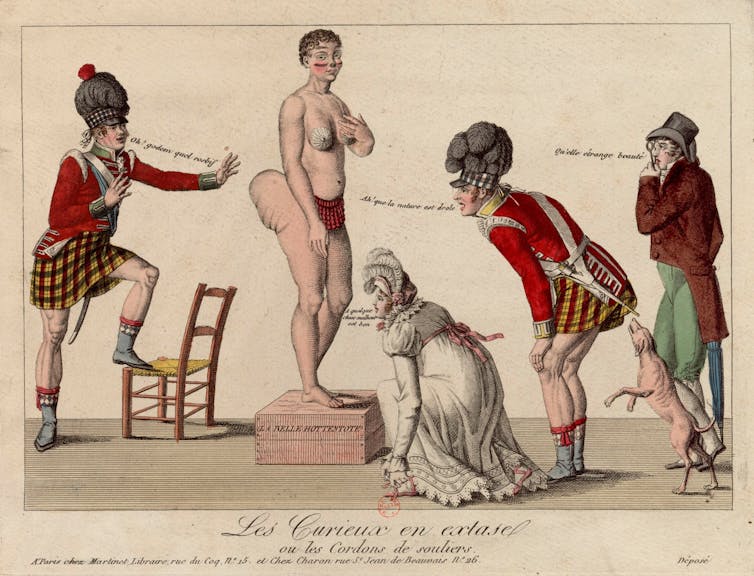

Often naked in these exhibitions, Baartman was sometimes suspended in a cage on stage while being poked, prodded and groped. Her body was characterized as grotesque, lascivious and obscene because of her protruding buttocks, which was due to a condition called steatopygia that occurs naturally among people in arid parts of southern Africa. She also had elongated labia, a physical feature derogatorily referred to as a “Hottentot apron."

Baartman had a naturally occurring condition called 'steatopygia.'

British Museum

Both became symbolic markers of racial difference, and many other women from this part of Africa were trafficked to Europe for white entertainment. Because they diverged so drastically from dominant ideas of white feminine beauty, Baartman's features were exoticized. Her voluptuous and curvaceous body – mocked and shamed in the West – was also described in advertisements as the “most correct and perfect specimen of her race."

The Baartman ideal

Of course, Black women's bodies vary; there is no monolithic – nor ideal – type.

Nonetheless, there is a strong legacy of the curvaceous ideal, more so than in other races.

It persists to this day.

In my interviews, Black women revealed how they felt about Baartman's story, how they compared her to their own body image and what her legacy represents.

One American participant, Ashley, seemed to recognize how entrenched the Baartman ideal has become.

“[Baartman] was the platform for stereotypes," she said. “She set the trend for Black women [to] have these figures and … now these stereotypes are carrying through pop culture."

Mieke, a South African woman, described being proud of her proportions and the way they're connected to Baartman, saying, “I'm proud of my body because of the resemblance I feel it has with hers."

Exploitation or empowerment?

Today, the Baartman body can be advantageous, especially on social media, where Black women have the opportunity to produce content that's socially and culturally relevant to them and their audiences – and where users can make money off their posts.

On various platforms, women leverage their looks to obtain paid advertisements or receive free gifts, services or merchandise from various beauty and apparel companies. They're also more likely to gain more followers – and perhaps attract more wealthy suitors, depending on their ambitions – by hewing more closely to the contemporary Baartman ideal.

So you could argue that Black women are taking control of their objectification and commodification to earn money. They're also protesting the ideals of white mainstream beauty, seizing Baartman's exploitation and mockery and recasting her as a source of pride and empowerment on places like #BlackTwitter, Instagram and OnlyFans.

On the other hand, it cannot be denied that Baartman's image is rooted in a legacy that is engulfed by slavery, unwillful submission and colonialism. The white gaze that fetishized Baartman's body as exotic and overtly sexual was the same one that promulgated the stereotype that Black women were sexually promiscuous, lascivious and hypersexual.

While Baartman may not have been able to keep the cash people paid to ogle at her, Black women today can strive for her body type and make money off it. Once subjected to the mockery of an insidious white gaze, Baartman's physique is now profitable – as long as these women are comfortable with being objectified.

But is selling this body type always a form of empowerment? Would someone who wasn't already exploited do it?

This may explain why Black women today are conflicted when they think about Baartman.

Lesedi, from South Africa, highlighted this tension.

“I feel you do find girls like me who are not proud of what they see when they look in the mirror and they just feel like, 'I need to drop this off,'" she said. However she added that “you find other girls that are just so happy about it that they twerk. … I guess Sarah Baartman definitely does have an influence, but it's either positive or negative whether you're proud to have a bum."

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend.Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]![]()

Rokeshia Renné Ashley, Assistant Professor of Communication, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.