By Megan Culler Freeman, University of Pittsburgh

A 33-year old man was found to have a second SARS-CoV-2 infection some four-and-a-half months after he was diagnosed with his first, from which he recovered. The man, who showed no symptoms, was diagnosed when he returned to Hong Kong after a trip to Spain.

I am a virologist with expertise in coronaviruses and enteroviruses, and I've been curious about reinfections since the beginning of the pandemic. Because people infected with SARS-CoV-2 can often test positive for the virus for weeks to months, likely due to the sensitivity of the test and leftover RNA fragments, the only way to really answer the question of reinfection is by sequencing the viral genome at the time of each infection and looking for differences in the genetic code.

There is no published peer-review report on this man – only a press release from the University of Hong Kong – although reports say the work will be published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. Here I address some questions raised by the current news reports.

Why wasn't the man immune to reinfection?

Immunity to endemic coronaviruses – those that cause symptoms of the common cold – is relatively short-lived, with reinfections occurring even within the same season. So it isn't completely surprising that reinfection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, might be possible.

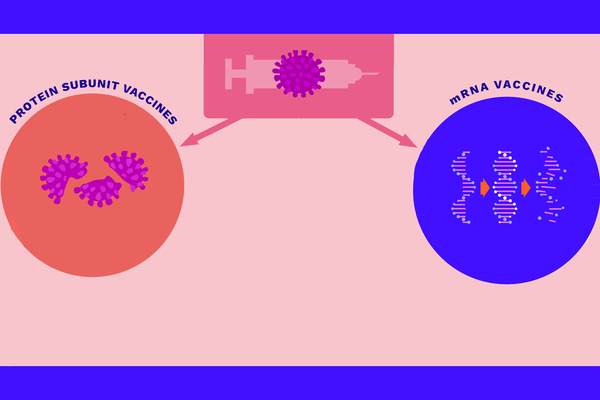

Immunity is complex and involves multiple mechanisms in the body. That includes the generation of antibodies – through what's known as the adaptive immune response – and through the actions of T-cells, which can help to educate the immune system and to specifically eliminate virus-infected cells. However, researchers around the world are still learning about immunity to this virus and so can't say for sure, based on this one case, whether reinfection will be a cause for broad concern.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend.Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

How different is the second strain that infected the Hong Kong man?

“Strain" has a particular definition when referring to viruses. Often a different “strain" is a virus that behaves differently in some way. The coronavirus that infected this man in Europe is likely not a new strain.

A STAT News article reports that the genetic make up of the sequenced virus from the patient's second infection had 24 nucleotides – building blocks of the virus's RNA genome – that differed from the SARS-CoV-2 isolate that infected him the first time.

SARS-CoV-2 has a genome that is made up of about 30,000 nucleotides, so the virus from the man's second infection was roughly 0.08% different than the original in genome sequence. That shows that the virus that caused the second infection was new; not a recurrence of the first virus.

The man was asymptomatic – what does that mean?

The man wasn't suffering any of the hallmark COVID-19 symptoms which might mean he had some degree of protective immunity to the second infection because he didn't seem sick. But this is difficult to prove.

I see three possible explanations. The first is that the immunity he gained from the first infection protected him and allowed for a mild second infection. Another possibility is that the infection was mild because he was presymptomatic, and went on to develop symptoms in the coming days. Finally, sometimes infections with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic – at the moment it is difficult to determine whether this was due to the differences in the virus or in the host.

What can we say about reinfection based on this one case?

Only that it seems to be possible after enough time has elapsed. We do not know how likely or often it is to occur.

Should people who have recovered from COVID-19 still wear a mask?

As we are still learning about how humans develop immunity to SARS-CoV-2 after infection, my recommendation is for continued masking, hand hygiene and distancing practices, even after recovery from COVID-19, to protect against the potential for reinfection.![]()

Megan Culler Freeman, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Fellow, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.