By Andrew Read, Penn State and David Kennedy, Penn State

The first drug against HIV brought dying patients back from the brink. But as excited doctors raced to get the miracle drug to new patients, the miracle melted away. In each and every patient, the drug only worked only for a while.

It turned out the drug was very good at killing the virus, but the virus was even better at evolving resistance to the drug. A spontaneous mutation in the virus' genetic material prevented the drug from doing its work, and so the mutant viruses were able to replicate wildly despite the drug, making the patients sick again. It took another decade before scientists found evolution-proof therapies.

Could the same thing happen to a COVID-19 vaccine? Could a vaccine that is safe and effective in initial trials go on to fail because the virus evolves its way out of trouble? As evolutionary microbiologists who have studied a poultry virus that has evolved resistance to two different vaccines, we know such an outcome is possible. We also think we know what it takes to stop it. COVID-19 vaccines could fail – but if they have certain properties, they won't.

History of vaccine resistance

For the most part, humanity has been lucky: Most human vaccines have not been undermined by microbial evolution.

For instance, the smallpox virus was eradicated because it never found a way to evolve around the smallpox vaccine, and no strain of the measles virus has ever arisen that can beat the immunity triggered by the measles vaccine.

But there is one exception. A bacterium that causes pneumonia managed to evolve resistance against a vaccine. Developing and replacing that vaccine with another was expensive and time-consuming, with seven years between the initial emergence of resistant strains and the licensing of the new vaccine.

There haven't been other failures for human vaccines yet, but there are hints that viruses, bacteria and parasites can evolve or are evolving in response to vaccination. Escape mutants that are able to evade vaccine-induced immunity are regularly seen in the microbes that cause hepatitis B and pertussis.

For such human diseases as malaria, trypanosomiasis, influenza and AIDS, vaccines have been hard or impossible to develop because the microbes that cause those diseases evolve so fast. In agricultural settings, animal vaccines are frequently undermined by viral evolution.

What would it look like?

If SARS-CoV-2 evolves in response to a COVID vaccine, there are several directions it could take. The most obvious is what happens with the flu virus. Immunity works when antibodies or immune cells bind to molecules on the surface of the virus. If mutations in those molecules on the surface of the virus change, antibodies can't grab on to them as tightly and the virus is able to escape. This process explains why the seasonal flu vaccine needs updating each year. If this happens, a COVID vaccine would need frequent updating.

But evolution might head off in other directions. It would be better for human health, for example, if the virus evolves a stealth mode, perhaps by reproducing slowly or hiding in organs where immunity is less active. Many pathogens that cause barely noticeable chronic infections have taken this tack. They avoid detection because they do not cause acute disease.

A more dangerous avenue would be if the virus evolved a way to replicate more quickly than the immunity generated by the vaccine. Another strategy would be for the virus to target the immune system and dampen vaccine-induced immunity.

Many microbes can survive inside the human body because of their exquisite ability to interfere with our immune systems. If SARS-CoV-2 has ways of even partially disabling human immunity, a COVID vaccine could favor mutants that do it even better.

Evolution-proof vaccines

Before COVID came along, the two of us compared vaccines that keep working with vaccines that have been undermined by pathogen evolution.

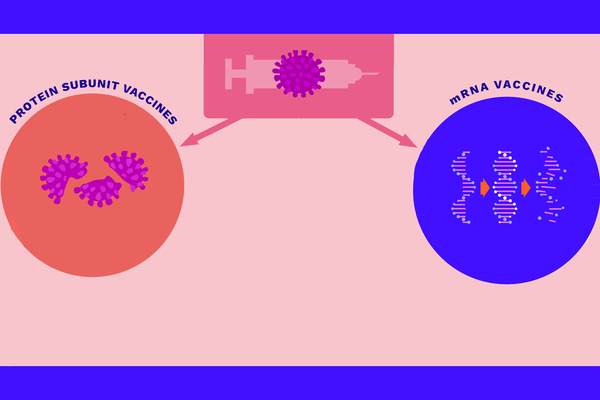

It turns out that truly evolution-proof vaccines have three features. First, they are highly effective at suppressing viral replication. This stops further transmission. No replication, no transmission, no evolution.

Second, evolution-proof vaccines induce immune responses that attack several different parts of the microbe at the same time. It is easy for a single part of the virus to mutate and escape being targeted. But if many sites are attacked at once, immune escape requires many separate escape mutations to occur simultaneously, which is almost impossible. This has already been shown in the laboratory for SARS-CoV-2. There the virus rapidly evolved resistance to antibodies targeting a single site, but struggled to evolve resistance to a cocktail of antibodies each targeting multiple different sites.

Third, evolution-proof vaccines protect against all circulating strains, so that no others can fill the vacuum when competitors are removed.

Will a COVID vaccine be evolution-proof?

Around 200 COVID vaccine candidates are at various stages of development. It is too soon to know how many of them have those evolution-proofing features.

Fortunately we don't need to wait until a licensed vaccine fails to find out. A bit of extra effort during vaccine trials can go a long way to working out whether a vaccine will be evolution-proof. By swabbing people who have received the experimental vaccine, scientists can tell how far virus levels are suppressed. By analyzing the genome of any virus in vaccinated people, it might be possible to see evolutionary escape in action. And by taking blood from vaccinees, we can work out in the lab how many sites on the virus are being attacked by vaccine-induced immunity.

[Deep knowledge, daily.Sign up for The Conversation's newsletter.]

Clearly, the world needs COVID vaccines. We believe it is important to pursue those that will keep working. Likely, many candidates in the current portfolio will. Let's work out which those are in clinical trials and go with them. Vaccines that provide only temporary relief leave people vulnerable and take time and money to swap out. They may also negate other vaccines should viruses evolve that are resistant to several vaccines at once.

Today, the world has insecticide-resistant mosquitoes and crop pests, herbicide-resistant weeds, and an antibiotic resistance crisis. No need for history to repeat itself.![]()

Andrew Read, Evan Pugh University Professor of Biology and Entomology, Eberly Professor of Biotechnology, Director, Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Penn State and David Kennedy, Assistant Professor of Biology, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.