As told to Nicole Audrey Spector

I became sexually active when I was really young — just 13 years old. I probably wasn’t emotionally mature enough for sex, but I had a boyfriend I trusted. We used birth control, but not condoms, so we had no protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Though I didn’t worry much about getting a disease through sex — because I believed my boyfriend was having sex only with me — I did make sure I was tested annually for STIs, including HIV.

At 13, my HIV test came back negative. Same at age 14 and 15. But 10 days before my 16th birthday, on November 7, 1996, I got a call from my doctor’s office after my HIV test. They needed me to come in to go over my results in person. I knew that meant I was positive.

I didn’t want anyone to know, so I took the bus to the doctor’s office alone.

My doctor told me that I was indeed HIV-positive. I was crushed and terrified. I didn’t know much about HIV and AIDS other than what I’d seen in the movie “Philadelphia,” which was hardly uplifting and certainly not inclusive of women. It was all images of frail men.

The doctor sent me on my way with some paperwork to fill out for a health clinic that specialized in treating people with HIV.

“I’m sorry, but there’s nothing we can do for you here in my practice,” the doctor said.

When I got home, I told my mother the results. I don’t remember much other than her screaming at me, shaming me, blaming me and pounding on the front door.

My boyfriend wasn’t any kinder. When I told him, he accused me of cheating — something I hadn’t done. He got tested soon after and was also HIV-positive. We stayed together for years after, but the relationship was unhealthy and sometimes abusive.

A few months after my diagnosis, I began taking a lot of medication to keep the disease at bay. It made me horribly sick to my stomach, and to this day, I can’t even think about it without getting queasy.

Life was already pretty lonely for me. I didn’t have a lot of friends and I had no one I could turn to in my family for support. But life got much lonelier after my diagnosis. I felt empty inside.

For all of my childhood until that point, succeeding in school had been my top priority. But once I was diagnosed, my academic ambition died, and I failed all my classes. As a brutal reminder of my defeat, my mother framed and hung my report card filled with F’s.

As the years passed, I became less and less invested in caring for myself. I didn’t begin taking my medications regularly until I learned I was pregnant with my daughter in 2000. I wanted to be well for her, and for her to be healthy inside me. Amazingly, despite having two HIV-positive parents, my darling Daniella was born HIV-negative.

Once I had Daniella, I stopped taking my medication again. I didn’t like it, and I felt like there was no point since I wasn’t pregnant anymore.

When Daniella was still a baby, I met Jason. He was a friend of my brother’s, and at first we didn’t quite hit it off. But over time, we bonded deeply. By then, Daniella’s father and I were long separated. Jason and I began dating.

I had unprotected sex with Jason, but didn’t tell him I was HIV-positive. I’ve spent some time wondering why I didn’t tell him. I think I was just so angry toward men — mostly from having been molested by my stepfather in the past — that I didn’t care in the moment.

Jason ended up finding out I was HIV-positive through someone else. He was upset that I hadn’t told him myself. But he still wanted to be with me, and we entered into the first truly loving relationship of my life.

As our relationship progressed, Jason became concerned that I wasn’t taking my medication. He told me that I needed to take it. I promised him I would — for him, for Daniella.

He looked at me and said, “No, you have to love yourself enough to take your medicine for you.”

It was a breakthrough moment.

Loving myself had never been important to me, and frankly, it was difficult to do after a lifetime of abuse. I started going to therapy and support groups for women living with HIV. I learned how to put myself first and recognize that if I don’t care for myself, I can’t really care for anyone else.

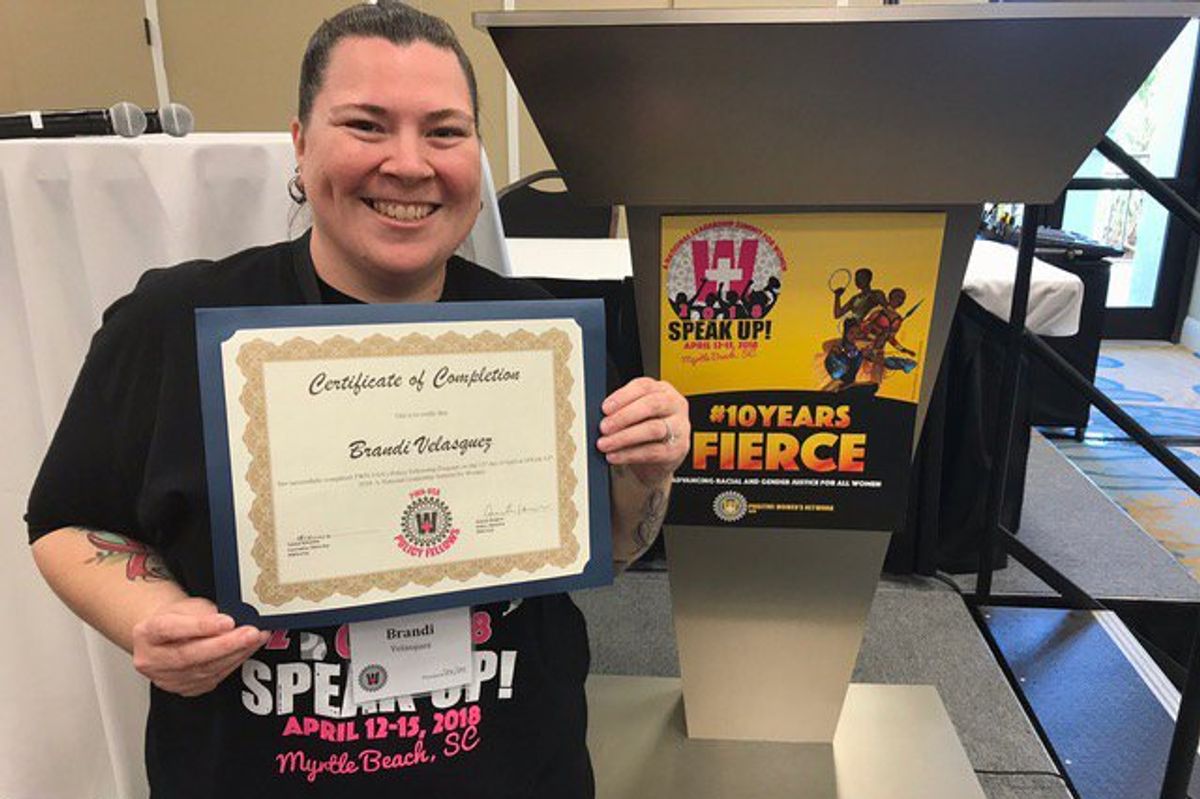

Jason and I got married and we’ve been together for 21 years now. I take my medication the way I’m supposed to, and the side effects aren’t as bad as they used to be. I also continue to deepen my relationship with the women’s HIV community. I’ve met so many wonderful women throughout the years. Unfortunately, I’ve lost many of them to AIDS, but their impact on my life is everlasting.

My husband asked me today, “What is your ultimate goal?”

He was referring to my advocacy work, which focuses not only on women with HIV, but also on the HIV-negative family members of those living with HIV. This is a challenging journey for them, too. They also deserve to be heard and respected in the HIV community.

But to answer Jason’s question: My ultimate goal is leaving a legacy behind that someone can look at and say, “She may have been only one person, but she made a difference in the world.”

This resource was created with support from Gilead.

Have a Real Women, Real Stories of your own you want to share? Let us know.

Our Real Women, Real Stories are the authentic experiences of real-life women. The views, opinions and experiences shared in these stories are not endorsed by HealthyWomen and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HealthyWomen.

- Living with HIV: What Women Need to Know, as Told by Maria Davis ›

- Your Words Can Make a Difference in the Fight Against HIV Stigma ›

- From Shame to Advocacy: My Decades-Long Journey Living — and Thriving — With HIV ›

- HIV, Aging and Whole Person Care ›

- I Believe I’m Aging Faster Because I Have HIV ›