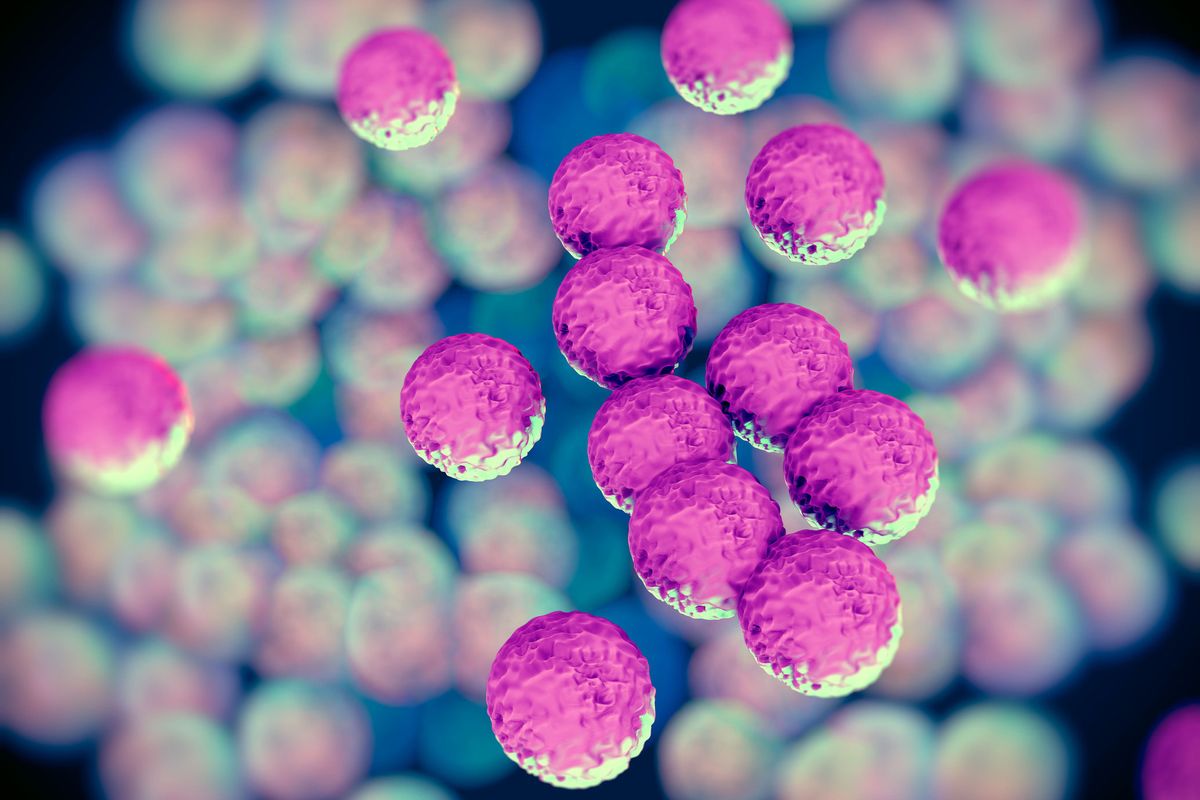

Trillions of microscopic bacteria, viruses and fungi live on our skin, in our mouths, in our guts and throughout our bodies. Most of them are harmless and some are beneficial, but a handful of them are pathogenic, meaning they produce diseases or infections.

The discovery of antimicrobial drugs, a group of drugs that includes antibiotics and antifungals, was one of the crowning achievements of the last century, as it allowed the medical community to treat diseases and infections that had previously killed countless people. For example, it's been estimated that penicillin, one of the first antibiotics created, has saved at least 200 million lives since it was first used as a medicine during World War II.

Today, most of us take for granted the idea that antibiotics will combat many common bacterial infections. But imagine taking penicillin for strep throat only to find that it no longer works — and then being prescribed a succession of other antibiotics only to find that none of them work. Unfortunately, this is precisely what we're up against as we enter an era in which many lifesaving drugs are no longer capable of fighting certain pathogens.

A year ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a concerning report about the existential threat of antibiotic resistance (AR), or antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which happens when pathogens develop defenses and fight back against the antibiotics designed to kill them. The inability to destroy such germs makes treating certain infections difficult, if not impossible.

The Infectious Disease Society of America considers antibiotic resistance a public crisis. The CDC goes one step further, calling it one of the biggest public health challenges of our time, and the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies AMR as "one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity."

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 era presents new AR and AMR challenges. While last year's CDC report should have sounded a warning shot around the world, the pandemic has directed attention, energy and resources away from the issue.

Why are antimicrobial drugs becoming resistant?

Every year in the United States, at least 2.8 million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection — and another 35,000 people die.

The crisis has been caused by a number of factors, including the increased use — and misuse — of antibiotics. The CDC believes that at least 30% of prescribed antibiotics in the United States are unnecessary. This is caused in large part by many health care providers being too liberal in doling out prescriptions. A whopping 41% of prescriptions for antibiotics, for example, are given to treat respiratory illnesses, despite the fact that many respiratory infections — common colds, bronchitis and the ilk — are caused by viruses, which can't be destroyed by antibiotics.

In addition, many patients simply don't follow the treatment regimens their health care providers prescribe, or they ask for antibiotics when they don't need them. Further worsening the crisis, many people self-prescribe and take leftover prescriptions or antibiotics prescribed to family or friends. By taking antibiotics inappropriately or when they don't need them, people raise their risk of experiencing potentially dangerous side effects, including developing AR or AMR.

How the pandemic has created new challenges

The pandemic may have increased the threat of AR and AMR. Many patients exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms at hospitals receive antibiotics to reduce the chance of getting a bacterial infection. For instance, during March and April in Michigan, over half of patients hospitalized with suspected COVID-19 were given antibiotics as a precautionary measure against bacterial infections. Later testing would show that 96.5% of them did not have a bacterial infection but had COVID-19, a virus that can't be destroyed by antibiotics.

Giving unnecessary antibiotics in a hospital not only increases the risk of developing drug-resistant pathogens, it accelerates the rate at which some of these resistant pathogens are spread. This is a big problem, because even before the pandemic, one of the biggest risks for getting an AR or AMR-associated illness such as MRSA, sepsis or C. diff was staying in a hospital or other health care facility.

The medical and health community is simply not equipped to face the AR and AMR challenge. The United States has withdrawn its support for WHO, which believes we must immediately act to protect the future from AR and AMR. It doesn't help that there's low public awareness about the extreme danger of drug-resistant pathogens.

How can we fight the problem?

Fortunately, there is a way forward. The National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (CARB), 2020-2025, presents a number of specific actions the U.S. government will take over the next five years to diminish AR and AMR. The plan, which is based on previous action plans and national strategies for CARB, has prioritized studying and collecting data about antibiotic resistance as well as preventing and slowing the spread of drug-resistant infections. These actions are being observed through the lens of One Health, a collaborative approach that works at local, regional, national and global levels to increase healthy outcomes for people, plants and animals.

To prevent a post-antibiotic era from becoming our dystopian future, we need to act now. In September, Sens. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., and Todd Young, R-Ind., introduced the PASTEUR Act, bipartisan legislation to help deal with this crisis. For the first time, this bipartisan legislation proposes establishing a subscription program for antibiotics, meaning the federal government could provide funds to companies developing new, critically needed antimicrobial drugs.

It is vitally important that the government be able to do this. It takes years to develop antibiotics, and we simply don't have time to wait as current drugs lose their efficacy against drug-resistant superbugs. In addition, without a subscription program, there is little incentive for companies to research new antibiotics, because it's a huge investment with a risk of no payback — there simply isn't a big market for new antibiotics, which are only used when older drugs fail.

In January, a new presidential administration will enter the White House, and many new legislators at all levels of government will be sworn in. Both new and incumbent lawmakers must prioritize antimicrobial resistance as a cornerstone of their policy initiatives — beginning with passing the PASTEUR Act. But government can't do it alone. We need a coordinated effort between government, industry and consumers to work toward solutions to this existential threat.

There's no time to waste.

- Why Antimicrobial Resistance Is a Threat We Need to Take Seriously - HealthyWomen ›

- Antimicrobial Resistance: An Emerging Public Health Threat - HealthyWomen ›

- Fast Facts: What You Need to Know About Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) - HealthyWomen ›

- Clinically Speaking: Important Questions to Ask About Antimicrobial Resistance - HealthyWomen ›

- Antimicrobial Resistance Is Bad News for Everyone, but May Hurt Some Communities More Than Others - HealthyWomen ›