As told to Erica Rimlinger

My three children and I had an easy time breastfeeding, and I nursed my children for as long as possible. Friends teased, “Those babies are old enough to ask for a soda,” but I didn’t care. I’m an insurance agent by trade and a health advocate by passion. I taught exercise classes for pregnant women and provided lactation education for women in the WIC program. I’m a cheerleader for wellness, and I promote the health-enhancing benefits of breastfeeding for moms and babies. On the road of health, my lane is prevention.

When a hard lump appeared while I was nursing my third son, I thought I had a clogged milk duct. In my years of breastfeeding and working with breastfeeding women, I’d seen clogged milk ducts, but I’d never had one before. The normal remedies of warm compression and massage didn’t work, so, puzzled, I went to the doctor.

I’d recently moved from Rochester, New York, to Houston, Texas, to get my degree in kinesiology with a focus on health coaching at Texas Woman’s University (TWU). I lived near Texas Medical Center, a block away from the TWU campus. With no private healthcare provider (HCP), I went to TWU’s Student Health Office, which was run by the University of Texas. To my surprise, the HCP told me I needed a mammogram. Then, after seeing the mammogram, she told me to get an appointment with an oncologist.

“Why would I see an oncologist for a breastfeeding issue?” I asked. “Tell me straight. What is going on?” I tried to get the HCP to look me in the eye. She avoided my gaze and my question, and said, “If someone says you don’t need a mastectomy, they are lying to you.”

I was 43 years old and a healthy mom. I exercised six days a week. I never took or needed to take medicine, even an aspirin. Now, the word “oncologist” hung in the air like a ghost. My father and his two brothers had died of pancreatic cancer. I knew what an oncologist did.

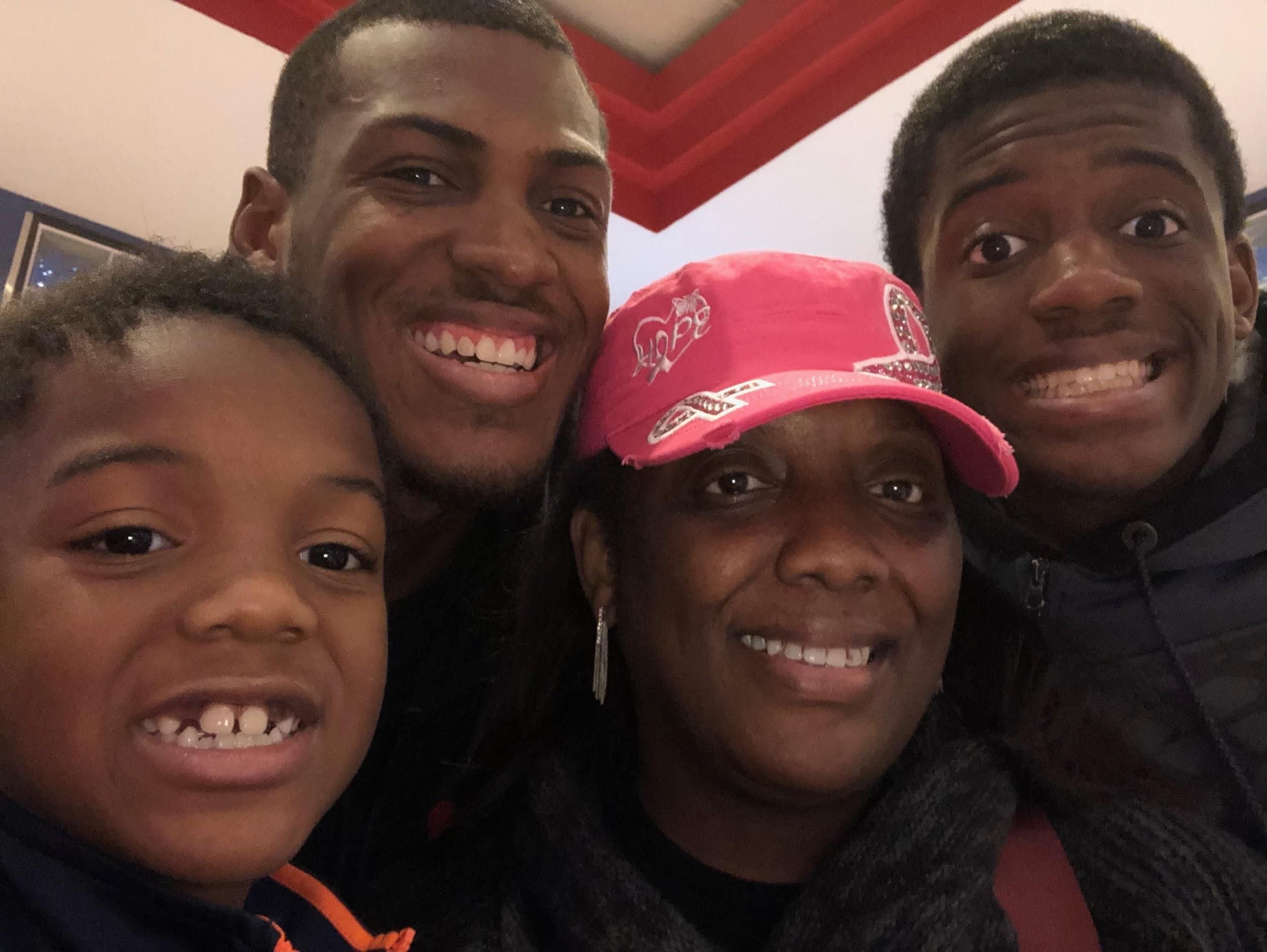

Tamiko Byrd with her children, 2022. (Photo/Cocoa Rae David)

Two weeks later, I sat at a round conference table at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center with a team of five medical professionals. I got my straight answer. I’d undergone a full day of testing and learned I had stage 4 breast cancer. My left breast was riddled with tumors that had metastasized to my shoulder blade.

I remembered what my sister, a nurse practitioner, said when our father was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer: “There’s no stage 5.” That day, my sister was on a business trip in Costa Rica when I called and told her. She fainted.

I felt faint, too, but I had a fight to win. Within a week, my mom and sister arrived in Houston to support my treatment, which began almost immediately with chemotherapy.

I now felt just as sick as my diagnosis implied. I thought I’d known what fatigue was, but I didn’t. I thought I knew how sick I could be and survive, but I didn’t. I lost my hair, and my eyebrows and eyelashes: the essence of my womanhood. The cancer center had a beauty salon where they shaved me, so I wouldn’t have to watch my hair fall out strand by strand. I silently prayed, “It’s just you and me, God! I’m scared. I don’t want to die, God!”

I had been working 30 hours a week while I attended school. My health coverage would have kicked in after 90 days, but I was diagnosed with cancer the week before coverage started, so I was denied coverage. Fortunately, I worked in insurance for years, and I knew I could appeal. As I worked, attended school, raised my sons and fought for my life with every cell in my body, I also went to battle with the health insurance company, appealing its decision. I was extremely and unusually fortunate that the hospital allowed me to continue treatment during my appeal. I would, after fighting for months, ultimately win the appeal. In the meantime, I applied for Medicaid and received it.

I know that if I didn’t happen to have a background in insurance, I never could have navigated the complex and time-consuming appeal process. I could barely manage it in the condition I was in.

I lost feeling in my toes and fingers. My joints ached. My fingernails and teeth loosened. But that wasn’t the worst of it. After my fifth round of chemotherapy, I lost control of my bowels at work. “This can’t be happening,” I sobbed, as I frantically rushed to clean up my mess in the bathroom with thin brown paper towels in between bouts of throwing up. I left work that day and never went back.

As tough as this was, I had faith that God was with me. I journaled my journey on Facebook to rally support and let my friends and family know we were fighting. From as far away as Africa, Rochester and Costa Rica, my community rallied with prayer circles, groceries, food, wigs, childcare help and more. Before my mastectomy, I threw a going-away party for my left breast. It was an intimate moment where I sang, cried, prayed and mourned for my breast. In Rochester, I had run a free community exercise program called Soul Fitness 10 hours per week. Now my old students were teaching me that when you give something to the community, the community gives back.

One month after my mastectomy, my grade point average dropped to 2.99 and I was automatically kicked out of school. For months, my spirits had been buoyed with love from my community and family. But I’d also been buoyed by the intellectual stimulation of school, by learning and keeping my mind active, and pursuing my dream of becoming a credentialed health coach.

I got angry. I had finally won my appeal against the insurance company, and now cancer was coming to take away my education. “You cannot have my mind, too,” I told cancer, and I filed an appeal at the school.

The dean and administration in the graduate studies program couldn’t figure out why I wanted to stay. “Why not just take some time to focus on regaining your health?” they asked. But I didn’t know if I ever would regain my health, and I wanted to spend whatever time I had left pursuing my dream.

I understood why people quit — but I was not going to. I would never quit.

The school relented, telling me, “OK, Ms. Byrd. We’ve never seen anyone fight this hard.” I was allowed to retake my semester. But they warned me: Financial aid wouldn’t cover it, and if I failed, I was out for good. I assured them I had fought so many battles, I could handle one more.

A week later, I went to the hospital for my scheduled full body scan.

The scan found no evidence of disease.

Fighting every step of the way, I’d beaten stage 4 breast cancer.

I returned to school. I received an A+ in my retaken classes. I graduated with an executive MBA and a master’s degree in kinesiology, the only student in my class to graduate with two degrees.

Now, when people ask me how I did it, I tell them all the lessons I learned in life prior to my cancer diagnosis were preparing me for a war I never thought I’d have to enter. The most important lesson was this: Keep fighting. Even when it seems like you won’t win — especially when it seems like you won’t win — fight anyway.

This resource is created with support from Merck & Sanofi.

- Don't Hide From Breast Cancer ›

- Breast Discharge as a Symptom of Breast Cancer - HealthyWomen ›

- Breastfeeding and Breast Cancer - HealthyWomen ›