Reviewed by Debbie Saslow, Ph.D.

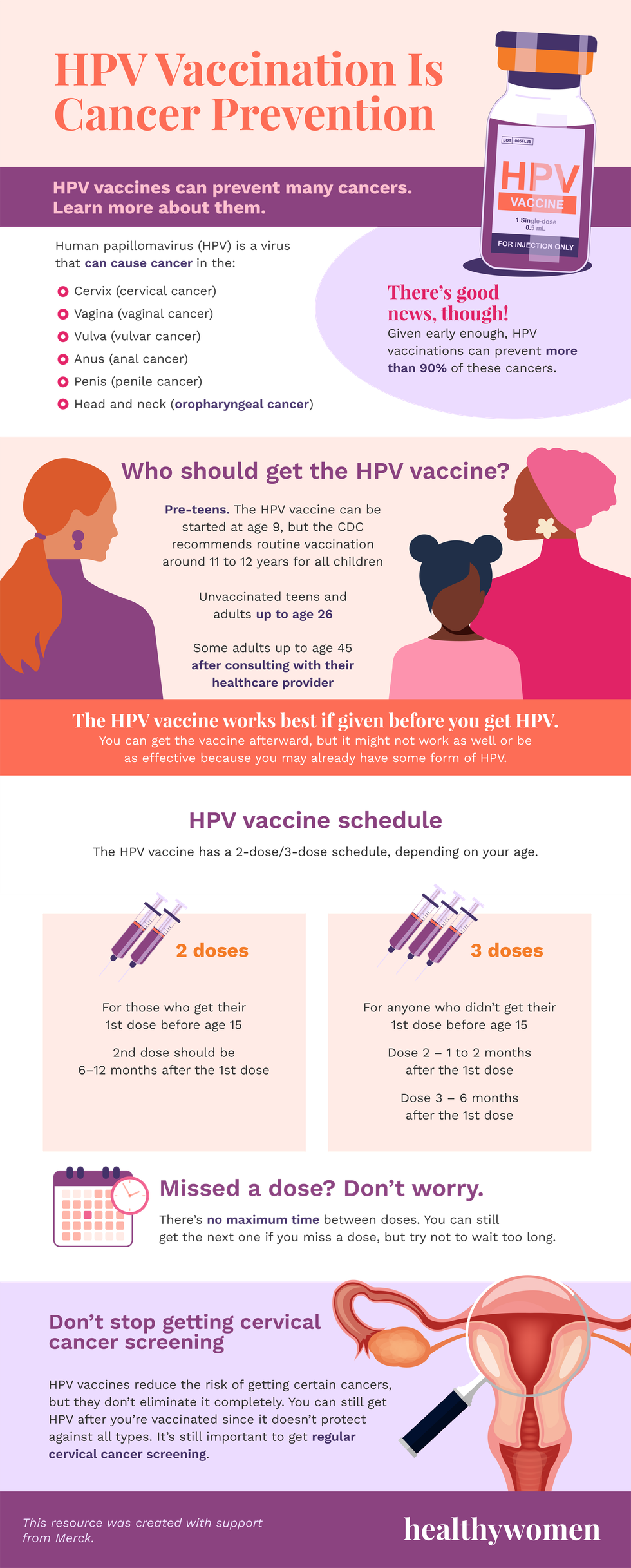

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a virus that can cause cancer in the:

- Cervix (cervical cancer)

- Vagina (vaginal cancer)

- Vulva (vulvar cancer)

- Anus (anal cancer)

- Penis (penile cancer)

- Head and neck ( oropharyngeal cancer )

There’s good news, though!

Given early enough, HPV vaccinations can prevent more than 90% of these cancers.

Who should get the HPV vaccine?

- Pre-teens : The HPV vaccine can be started at age 9, but the CDC recommends routine vaccination around 11 to 12 years for all children

- Unvaccinated teens and adults up to age 26

- Some adults up to age 45 after consulting with their healthcare provider

The HPV vaccine works best if given before you get HPV. You can get the vaccine afterward, but it might not work as well or be as effective because you may already have some form of HPV.

HPV vaccine schedule

The HPV vaccine has a 2-dose/3-dose schedule, depending on your age.

2 doses:

- For those who get their 1st dose before age 15

- 2nd dose should be 6–12 months after the 1st dose

3 doses:

- For anyone who didn’t get their 1st dose before age 15

- Dose 2 – 1 to 2 months after the 1st dose

- Dose 3 – 6 months after the 1st dose

Missed a dose? Don’t worry.

There’s no maximum time between doses. You can still get the next one if you miss a dose, but try not to wait too long.

Don’t stop getting cervical cancer screening

HPV vaccines reduce the risk of getting certain cancers, but they don’t eliminate it completely. You can still get HPV after you’re vaccinated since it doesn’t protect against all types. It’s still important to get regular cervical cancer screening .

This resource was created with support from Merck.

- Preventive Health Screenings for Women ›

- Human Papillomavirus, HPV ›

- Cervical Cancer Screening Can Save Your Life ›

- A Conversation About HPV & Cervical Cancer Screening ›

- Fast Facts: Here’s What You Need to Know About Cervical Cancer and HPV ›

- HPV Vaccine - HealthyWomen ›

- HPV Vaccines Around the World - HealthyWomen ›

- Las vacunas contra el VPH en todo el mundo - HealthyWomen ›