You wake up with a sore throat, stuffy nose, sinus pressure and a headache. You may suspect you have a sinus infection. To treat these unpleasant symptoms, you'd likely seek medical attention from a healthcare professional to receive a diagnosis and treatment so you can return to your normal daily activities. Pretty straightforward, right?

If only seeking medical care for postpartum depression (PPD) were as straightforward as seeking medical care for a sinus infection. So why is it more difficult for women to seek care for PPD?

Here are some potential hurdles women may face when seeking care for PPD and some tips for how to overcome them.

PPD may be thought of as an embarrassing condition.

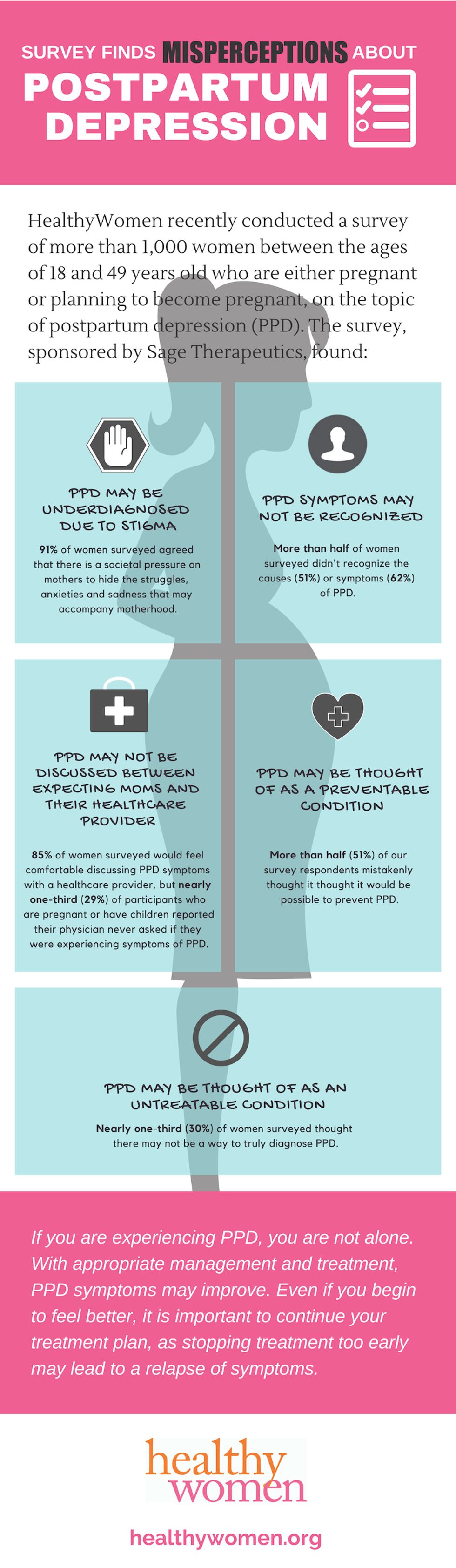

PPD, despite being the most common medical complication of childbirth, carries a stigma that may be at the root of why so many women don't share their PPD symptoms with a healthcare professional. HealthyWomen recently conducted a survey, sponsored by Sage Therapeutics, with more than 1,000 female respondents between the ages of 18 and 49 years old who are either pregnant or planning to become pregnant. The results showed 91 percent of the women surveyed agreed that there is a societal pressure on mothers to hide the struggles, anxieties and sadness that may accompany motherhood.

Since there can be significant stigma associated with mental health conditions, it might be daunting to think about sharing your symptoms with a healthcare professional. If you feel at all uncomfortable speaking up about what you are feeling, remember that you are experiencing a legitimate medical condition, and your healthcare provider should be able to recognize that. Some healthcare professionals might not be familiar with the high incidence of PPD – 29 percent of the women we surveyed who are pregnant or have children reported that their providers did not ask about or mention PPD symptoms. If that is the case for you, it's important that you feel comfortable describing potential PPD symptoms on your own, whether to your healthcare provider, partner, family members or friends.

PPD side effects may mask themselves as "normal" consequences of motherhood.

Some of the symptoms of PPD, like irritability, excessive crying or loss of energy, could be brushed off as normal side effects of motherhood. These are also symptoms of what is known as "baby blues," which affect about 80% of new mothers; however, if they persist for more than two weeks, they might be from PPD. Other more grave symptoms of PPD, like thinking about harming yourself or your baby, are less frequent but require urgent discussion with your healthcare provider or family. In our survey, only 38 percent of those surveyed were aware that having suicidal thoughts can be a symptom of PPD.

PPD signs and symptoms can present in many ways, including:

- Depressed mood or severe mood swings

- Excessive crying

- Difficulty bonding with your baby

- Withdrawing from family and friends

- Loss of appetite or eating much more than usual

- Inability to sleep (insomnia) or sleeping too much

- Overwhelming fatigue or loss of energy

- Reduced interest and pleasure in activities you used to enjoy

- Intense irritability and anger

- Fear that you're not a good mother

- Hopelessness

- Feelings of worthlessness, shame, guilt or inadequacy

- Diminished ability to think clearly, concentrate or make decisions

- Restlessness

- Severe anxiety and panic attacks

- Thoughts of harming yourself or your baby

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

Speaking with your healthcare provider about any postpartum symptom, even if you think it is a normal part of motherhood, may help to identify and then treat PPD before severity of symptoms potentially increases.

PPD may not be thought of as a real condition.

More than half of our survey respondents thought it would be possible to prevent PPD. PPD is not preventable. The thought that it is a preventable condition may place blame on the mother if she experiences symptoms of or is diagnosed with PPD.

Any woman who is pregnant or has recently had a baby is at risk for PPD. However, you may have an increased risk of developing PPD if any of the following apply to you:

- You have a history of depression, either during pregnancy or at other times.

- You have bipolar disorder.

- You had postpartum depression after a previous pregnancy.

- You have family members who've had depression or other mood disorders (family history).

- You've experienced stressful events during the past year, such as pregnancy complications, illness or job loss.

- Your baby has health problems or other special needs.

- You have twins, triplets or other multiple births.

- You have difficulty breastfeeding.

- You're having problems in your relationship with your spouse or significant other.

- You have a weak support system.

- You have financial problems.

- The pregnancy was unplanned or unwanted.

We all can help spread the word that PPD is a medical condition. The more we openly talk about it, the more people will accept (and respect) it for what it is.

PPD may be difficult to diagnose.

There's also some confusion among women about how PPD is diagnosed. Thirty percent of women surveyed didn't know how or whether healthcare providers truly diagnose PPD. Many believe there is no concrete diagnosis for PPD, a misconception that may lead to the assumption that PPD is "all in a woman's head." PPD is a medical condition that can be diagnosed.

To diagnose PPD, a healthcare professional may:

- Conduct a depression screening that may include asking you questions or having you fill out a questionnaire

- Order other tests, if warranted, to rule out other causes for your symptoms

Women may believe there is no treatment for PPD.

Let's go back to the sinus infection example. If you found out you had a sinus infection, but a healthcare professional told you there was no way to treat it, would you even care to receive a diagnosis? This seems to be the case for some women when they think about PPD; they may feel that there's no point in getting a PPD diagnosis if there's no way to treat the condition.

PPD treatment options do exist and include:

- Talk therapy: This may help women discover ways to cope with their feelings, solve problems, set realistic goals and respond to situations in an effective way

- Antidepressants: A healthcare professional may recommend an antidepressant. For those breastfeeding, some antidepressants have minimal risk of affecting your baby

With appropriate treatment plans, PPD symptoms may improve. Even if you begin to feel better, it is important to continue treatment, as stopping treatment too early may lead to a relapse of symptoms.

If you are experiencing PPD, you are not alone. We hope that this information will help you and other women understand that there are resources, information and treatments available for those experiencing the symptoms described in this article.

- When Postpartum Depression Hit, I Heard Only the Lies My Depression Told Me - HealthyWomen ›

- When Postpartum Depression Hit, I Heard Only the Lies My Depression Told Me - HealthyWomen ›

- I Lost My Daughter to Postpartum Depression - HealthyWomen ›

- Difference Between Postpartum Depression and "Baby Blues" - HealthyWomen ›

- Recognizing Postpartum Depression - HealthyWomen ›

- Having Another Baby After Postpartum Depression - HealthyWomen ›