Before my mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease at age 68, I rarely gave the disease a second thought. It was something that happened to other people, not a devastating, incurable illness that afflicts nearly 50 million people worldwide and could affect my own family.

Now I'm intimate with the symptoms and progression of this brutal form of dementia, I often worry whether it lies in my future, too. I've watched my mom decline rapidly over the past six years, from a vibrant woman who cross-country skied, played with her grandchildren, and spoke conversational Italian to a barely-verbal patient who struggles to walk and feed herself.

With my mom's diagnosis, the likelihood of me getting the disease has increased. "Genetics contributes between 35 and 65 percent of the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease," wrote Nancy Mace, MA, and Peter Rabins, MD MPH, in their book, "The 36-Hour Day: A Family Guide to Caring for People Who Have Alzheimer Disease, Other Dementias, and Memory Loss," an indispensable resource for families that I wish I had discovered years earlier.

And because I'm a middle-aged woman looking ahead to menopause, I was alarmed to learn about recent studies that show the menopause transition may be a risk factor for Alzheimer's.

An overactive mind can quickly translate medical statistics into a feeling of personal doom. But I've found that instead of agonizing, delving deeper into the research gives me a greater sense of control. Learning more about the menopause-Alzheimer's connection has calmed some of my anxiety and helped me focus on what I can do to improve my cognitive health now, in the critical window before menopause.

Women make up two-thirds of patients living Alzheimer's worldwide, and it's not just because we live longer. Alzheimer's is thought to begin in the brain fifteen to twenty years before clinical diagnosis. If you do the math, working backwards from the average age of Alzheimer's diagnosis (mid-70s), the inception of the disease coincides with the average age of menopause (mid-50s). Only recently have researchers begun studying the specific mechanisms that may affect women's disproportionate susceptibility to Alzheimer's.

"One of the most startling facts about the disease is that a 45-year-old woman has a one-in-five chance of developing Alzheimer's during her remaining life, while a man of the same age has only a one-in-ten chance," wrote Lisa Mosconi, PhD, in her forthcoming book "The XX Brain: The Groundbreaking Science Empowering Women to Maximize Cognitive Health and Prevent Alzheimer's Disease." Mosconi directs the Women's Brain Initiative at Weill Cornell Medical College and is associate director of the first Alzheimer's Prevention Clinic in the United States. She has made female brain health her life's work, leading a revolutionary brain imaging study that showed markedly reduced brain activity in post-menopausal women.

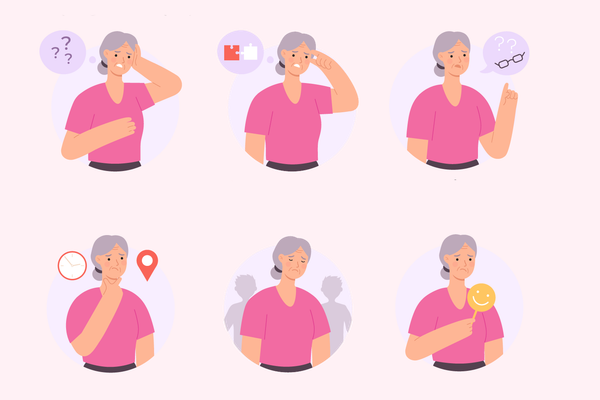

But how, exactly, does menopause impact a woman's cognitive health? Complaints about "brain fog," difficulty concentrating, and memory lapses are all common during the menopause transition and early menopause, according to Barb DePree, MD, a gynecologist and women's health provider who also serves on HealthyWomen's Women's Health Advisory Council. Numerous studies have shown that women's memory declines significantly from the premenopausal to the post-menopausal stage, said DePree.

At this point in my research, I felt panicked. But Mosconi's book clarified that menopause does not cause Alzehimer's—rather it makes the brain more vulnerable to degenerative changes. And, DePree emphasized that the link between menopause and Alzheimers is a complex topic and that more research is needed before we truly understand the connection.

Hormones are powerful chemicals that affect nearly every process in our bodies and brains. Sex hormones, which include estrogen, progesterone and testosterone, all modulate aspects of brain function and impact our attention, memory, and cognition throughout our lifetimes. Estrogen, in particular, is "a major, if not the major, hormonal driver of women's brain health," wrote Mosconi in "The XX Brain." Estrogen serves as a neuro-protectant, she explained, "playing a crucial defensive role in the brain by boosting the immune system, thereby shielding neurons from harm." Given the major impact of menopause on estrogen and the abundance of estrogen receptors in the brain, it's no wonder that women's brain function is often negatively impacted by menopause.

I confess that learning about the effects on menopause on the brain, along with watching my Alzheimer's mother decline rapidly over the past six years, can fill me with gloom. So I asked DePree what therapeutic interventions could help slow down or even prevent Alzheimer's for pre- and peri-menopausal women.

"There is some evidence of possible benefit of hormone therapy in preventing Alzheimer's disease and dementia," said DePree in an email to HealthyWomen. She noted that in animal models, estradiol has seemed to protect against the neuropathy of Alzheimer's disease. Observational studies have suggested a potential decrease in Alzheimer's when patients begin hormone therapy at younger ages (within the first 5 to 10 years of menopause). She also cited the groundbreaking, cumulative 18-year study conducted by the Women's Health Initiative, in which double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials tracked health outcomes for women aged 50 to 79. The WHI study showed that women on estrogen therapy had a significantly lower risk of dying from Alzheimer's disease, compared with women taking the placebo.

I felt heartened by these studies, and even more hopeful at the news that our lifestyle choices play a significant role in our cognitive health. New research indicates that up to half of the causes of Alzheimer's disease can be attributed to modifiable risk factors, including diabetes mellitus, midlife hypertension, midlife obesity, smoking, depression, cognitive inactivity, and physical inactivity. DePree recommended that women address lifestyle changes before entering menopause, to improve our overall health and reduce cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.

Many of these lifestyle changes are straightforward, if challenging to sustain. DePree urged women to cultivate a strong social network and stay physically and mentally active. She also advised following a Mediterranean diet, not smoking, and limiting alcohol consumption. But if you had to choose a single step to protect your brain against Alzheimer's, she said, focus on exercise.

"The strongest evidence is likely in support of regular exercise to prevent cognitive decline," said Dr. DePree. As a yoga instructor and a lifelong athlete, I feel encouraged that I'm on the right path. Rather than fretting about a potential Alzheimer's diagnosis, I'm determined to keep moving.

- Dementia Can Happen to Anyone but Is Not a Normal Part of Aging ›

- Alzheimer’s Is Not a Normal Part of Aging ›

- Menopausal and Feeling Forgetful? Brain Fog Might Be to Blame ›

- Treatment Options for Alzheimer’s Disease ›

- Estrogen Can Substantially Decrease the Risk of Alzheimer's ›