By Melissa Hawkins, American University

After sustained declines in the number of COVID-19 cases over recent months, restrictions are starting to ease across the United States. Numbers of new cases are falling or stable at low numbers in some states, but they are surging in many others. Overall, the U.S. is experiencing a sharp increase in the number of new cases a day, and by late June, had surpassed the peak rate of spread in early April.

When seeing these increasing case numbers, it is reasonable to wonder if this is the dreaded second wave of the coronavirus – a resurgence of rising infections after a reduction in cases.

The U.S. as a whole is not in a second wave because the first wave never really stopped. The virus is simply spreading into new populations or resurging in places that let down their guard too soon.

To have a second wave, the first wave needs to end

A wave of an infection describes a large rise and fall in the number of cases. There isn't a precise epidemiological definition of when a wave begins or ends.

But with talk of a second wave in the news, as an epidemiologist and public health researcher, I think there are two necessary factors that must be met before we can colloquially declare a second wave.

First, the virus would have to be controlled and transmission brought down to a very low level. That would be the end of the first wave. Then, the virus would need to reappear and result in a large increase in cases and hospitalizations.

Many countries in Europe and Asia have successfully ended the first wave. New Zealand and Iceland have also made it through their first waves and are now essentially coronavirus-free, with very low levels of community transmission and only a handful of active cases currently.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories.Sign up for The Conversation's science newsletter.]

In the U.S., cases spiked in March and April and then trended downward due to social distancing guidance and implementation. However, the U.S. never reduced spread to low numbers that were sustained over time. Through May and early June, numbers plateaued at approximately 25,000 new cases daily.

We have left that plateau. Since mid-June, cases have been surging upwards. Additionally, the percentage of COVID-19 tests that are returning positive is climbing steeply, indicating that the increase in new cases is not simply a result of more testing, but the result of an increase in spread.

As of writing this, new deaths per day have not begun to climb, but some hospitals' intensive care units have recently reached full capacity. In the beginning of the outbreak, deaths often lagged behind confirmed infections. It is likely, as Anthony Fauci, the nation's top infectious-disease specialist said on June 22, that deaths will soon follow the surge in new cases.

Different states, different trends

Looking at U.S. numbers as a whole hides what is really going on. Different states are in vastly different situations right now and when you look at states individually, four major categories emerge.

- Places where the first wave is ending: States in the Northeast and a few scattered elsewhere experienced large initial spikes but were able to mostly contain the virus and substantially brought down new infections. New York is a good example of this.

- Places still in the first wave: Several states in the South and West – see Texas and California – had some cases early on, but are now seeing massive surges with no sign of slowing down.

- Places in between: Many states were hit early in the first wave, managed to slow it down, but are either at a plateau – like North Dakota – or are now seeing steep increases – like Oklahoma.

- Places experiencing local second waves: Looking only at a state level, Hawaii, Montana and Alaska could be said to be experiencing second waves. Each state experienced relatively small initial outbreaks and was able to reduce spread to single digits of daily new confirmed cases, but are now all seeing spikes again.

The trends aren't surprising based on how states have been dealing with reopening. The virus will go wherever there are susceptible people and until the U.S. stops community spread across the entire country, the first wave isn't over.

What could a second wave look like?

It is possible – though at this point it seems unlikely – that the U.S. could control the virus before a vaccine is developed. If that happens, it would be time to start thinking about a second wave. The question of what it might look like depends in large part on everyone's actions.

The 1918 flu pandemic was characterized by a mild first wave in the winter of 1917-1918 that went away in summer. After restrictions were lifted, people very quickly went back to pre-pandemic life. But a second, deadlier strain came back in fall of 1918 and third in spring of 1919. In total, more than 500 million people were infected worldwide and upwards of 50 million died over the course of three waves.

It was the combination of a quick return to normal life and a mutation in the flu's genome that made it more deadly that led to the horrific second and third waves.

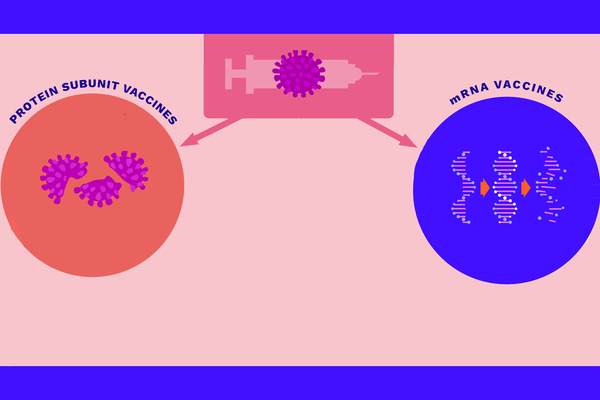

Thankfully, the coronavirus appears to be much more genetically stable than the influenza virus, and thus less likely to mutate into a more deadly variant. That leaves human behavior as the main risk factor.

Until a vaccine or effective treatment is developed, the tried-and-true public health measures of the last months – social distancing, universal mask wearing, frequent hand-washing and avoiding crowded indoor spaces – are the ways to stop the first wave and thwart a second one. And when there are surges like what is happening now in the U.S., further reopening plans need to be put on hold.![]()

Melissa Hawkins, Professor of Public Health, Director of Public Health Scholars Program, American University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.