By Nancy McGlasson

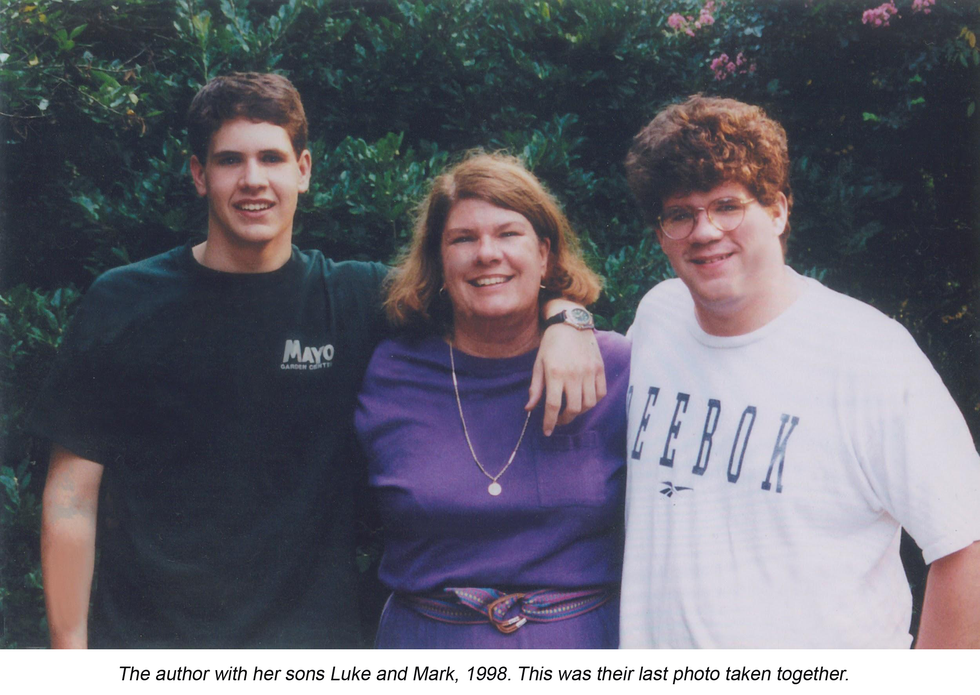

The phone rings. I don't want to answer but do because it's Anne Bonnyman. Her recent homily honoring my older son Mark still echoes in my head. He was almost 20 years old. Anne is our friend, the one Mark would have chosen to comfort a church full of people who don't understand why he died by suicide. We all blame others or feel guilt, or both. I haven't really slept in the week since he died, and now I spend nights in a place I call The Cave.

Although I'm frightened and unsafe, it's where I must go, in my mind, to try to understand why we lost him. At night I lie in bed searching for reasons he left us. I make a list, including what I did wrong. I'm not only a mom in mourning. I'm also angry at those who hurt my son and start another list for them. My name's near the top.

Sometimes I find The Cave in our small basement laundry room. I let myself cry — honestly, it's more of a keening — and hope Luke, my younger son who's 16 and asleep two floors up, won't hear. Sometimes I walk by the river to watch the geese begin their migrations. Mark, too, has flown away. When the sun rises, I put on my cheerful pretense for Luke, as he dons his smiling mask for me. Families protect one another when tragedy occurs.

Mark with Anne Bonnyman, 1995.

When Anne asks, "How's my Nancy?" we both cry. I tell her about The Cave and my nightly review of woulda/coulda/shoulda's, the lists I've drafted of reasons and people to blame.

"Why are you on those lists?" she asks.

"A mother saves her son. I failed."

I also share that something watches me in The Cave. I don't know what it is, but I sense and fear it.

Anne doesn't say, "Don't be silly! Get outta there!" Instead she offers, "What's it like? Help me see The Cave."

I describe its total darkness and stench. The rocky paths slimy as rotten cucumber. The air heavy with wet and cold.

"Well," she says, unfazed, "any furniture in there?"

"Furniture?"

"Since you're visiting so much, make it comfortable."

We begin with my grandmother's white split oak rocker that everyone loves and then clean up rubble while we discuss the lists. We bring flashlights so I don't fall as often. Whenever we say goodbye, Anne has a new request for The Cave's remodeling.

"Get that little Persian rug the boys always played Legos on!"

I join in. "I'll bring that pretty handmade quilt — second-place winner from the Norris Dam Craft Cooperative."

I imagine myself rocking back and forth in the dark in Grandmother's chair, warm under the quilt's colors. As I grow more comfortable in The Cave, I finish my lists. More than 100 names are on the sheets entitled "Who Killed Mark." Mine's still near the top.

I pull the quilt tighter and hunker down to research those I blame most. It is absolutely true that Mark was depressed for half his life and attempted suicide several times. If Death waited on top of a cliff, Mark climbed up to meet him all on his own. But some words from others I found online (and hidden in his room) might have encouraged him to seek death. Gave him a little push. I consider revenge.

"We need a fire!" Anne's next idea sends us scrambling to forage for wood and kindling. "Can we use some of those papers you've already read?" The fire catches immediately and smoke rolls out from The Cave's opening. Some of my anger at those I blame leaves with each puff. I look around to see if I can find the presence I've felt and realize I no longer fear it.

"More chairs?" I ask, and pull in rockers and quilts.

"Good," says Anne. "It's time to include more of us. You've kept many away. They've been hurt, too."

I invite wise women to visit us in The Cave. We throw logs on the fire. We talk about how much we miss Mark. What we should have done. What we did right. Luke and other wise men come too. I toss another log on the fire. I hear a crackle, and the sweet smell of pitch rises with the warm smoke.

As we begin to rock in silence, I realize I rarely hear about my friends' children. I don't open my heart to their sorrows or joys. They must find me so self-centered, wrapped tightly around my grief. Still, they remain loyal. I thank them, again and again.

One night Anne agrees, there's a watcher in The Cave. After we end our conversation, I give up plans for revenge in order to search and finally find Forgiveness, glimmering in the firelight. I welcome her.

Blame and guilt join anger and float away in the smoke. Only three names remain on the list. I've forgiven all the rest. I worry I'll never pardon those three. A friend says that sometimes we cannot forgive until we are asked for forgiveness. Those three have never asked. I await their requests and begin to forgive myself.

The Cave becomes a waiting room instead of a dead end. All the memories stored there make it my cherished space. So many memories are good ones. I hear Mark's easy laughter and remember his delphinium blue eyes. Oh, how they sparkled!

I recommend The Cave to anyone after tremendous loss, not only suicide. The sufferer must have an imagination, but once you make it yours, The Cave becomes a place where Forgiveness replaces anger, guilt, and blame. Peace and healing can then join her in The Cave with you.

More than 20 years later, I still visit on Mark's birthday or any day he would have celebrated. I go too, whenever his loss becomes unbearable again. Although it offers unexpected, truly miraculous comfort, even The Cave cannot heal every wound. I light the fire, and watch the bright flowers sewn on the quilt. They move as I rock.

The author with Mark, 1979

Resources

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please reach out to The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline toll-free number, 1-800-273-TALK(8255), which connects the caller to a certified crisis center near where the call is placed.