June Gruber, University of Colorado Boulder and Jonathan Rottenberg, University of South Florida

The mental health crisis triggered by COVID-19 is escalating rapidly. One example: When compared to a 2018 survey, U.S. adults are now eight times more likely to meet the criteria for serious mental distress. One-third of Americans report clinically significant symptoms of anxiety or clinical depression, according to a late May 2020 release of Census Bureau data.

While all population groups are affected, this crisis is especially difficult for students, particularly those pushed off college campuses and now facing economic uncertainty; adults with children at home, struggling to juggle work and home-schooling; and front-line health care workers, risking their lives to save others.

We know the virus has a deadly impact on the human body. But its impact on our mental health may be deadly too. Some recent projections suggest that deaths stemming from mental health issues could rival deaths directly due to the virus itself. The latest study from the Well Being Trust, a nonprofit foundation, estimates that COVID-19 may lead to anywhere from 27,644 to 154,037 additional U.S. deaths of despair, as mass unemployment, social isolation, depression and anxiety drive increases in suicides and drug overdoses.

But there are ways to help flatten the rising mental health curve. Our experience as psychologists investigating the depression epidemic and the nature of positive emotions tells us we can. With a concerted effort, clinical psychology can meet this challenge.

Reimagining mental health care

Our field has accumulated long lists of evidence-based approaches to treat and prevent anxiety, depression and suicide. But these existing tools are inadequate for the task at hand. Our shining examples of successful in-person psychotherapies – such as cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, or dialectical behavioral therapy for suicidal patients – were already underserving the population before the pandemic.

Now, these therapies are largely not available to patients in person, due to physical distancing mandates and continuing anxieties about virus exposure in public places. A further complication: Physical distancing interferes with support networks of friends and family. These networks ordinarily allow people to cope with major shocks. Now they are, if not completely severed, surely diminished.

What will help patients now? Clinical scientists and mental health practitioners must reimagine our care. This includes action on four interconnected fronts.

First, the traditional model of how and where a person receives mental health care must change. Clinicians and policymakers must deliver evidence-based care that clients can access remotely. Traditional “in-person” approaches – like individual or group face-to-face sessions with a mental health professional – will never be able to meet the current need.

Telehealth therapy sessions can fill a small part of the remaining gap. Forms of nontraditional mental health care delivery must fill the rest. These alternatives do not require reinvention of the wheel; in fact, these resources are already readily accessible. Among available options: web-based courses on the science of happiness, open-source web-based tools and podcasts. There are also self-paced, web-based interventions – mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is one – which are accessible for free or at reduced rates.

Democratizing mental health

Second, mental health care must be democratized. That means abandoning the notion that the only path to treatment is through a therapist or psychiatrist who dispenses wisdom or medications. Instead, we need other kinds of collaborative and community-based partnerships.

For example, given the known benefits of social support as a buffer against mental distress, we should enhance peer-delivered or peer-supported interventions – like peer-led mental health support groups, where information is communicated between people of similar social status or with common mental health problems. Peer programs have great flexibility; after orientation and training, peer leaders are capable of helping individual clients or groups, in person, online or via the phone. Initial data shows these approaches can successfully treat severe mental illness and depression. But they are not yet widely used.

Taking a proactive approach

Third, clinical scientists must promote mental health at the population level, with initiatives that try to benefit everyone rather than focusing exclusively on those who seek treatment. Some of these promotion strategies already have clear-cut scientific support. In fact, the best-supported population interventions, such as exercise, sleep hygiene and spending time outdoors, lend themselves perfectly to the needs of the moment: stress-relieving, mental illness-blocking and cost-free.

Finally, we must track mental health on the population level, just as intensely as COVID-19 is tracked and modeled. We must collect much more mental health outcome data than we do now. This data should include evaluations from mental health professionals as well as reports from everyday citizens who share their daily experiences in real time via remote-based survey platforms.

Monitoring population-level mental health requires a team effort. Data must be collected, then analyzed; findings must be shared across disciplines – psychiatry, psychology, epidemiology, sociology and public health, to name a few. Sustained funding from key institutions, like the NIH, are essential. To those who say this is too tall an order, we ask, “What’s the alternative?” Before flattening the mental health curve, the curve must be visible.

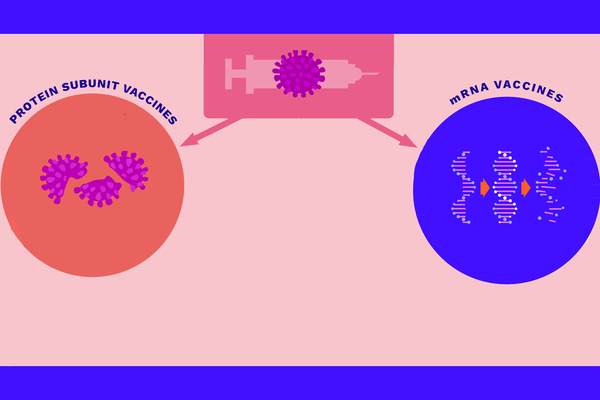

COVID-19 has revealed the inadequacies of the old mental health order. A vaccine will not solve these problems. Changes to mental health paradigms are needed now. In fact, the revolution is overdue.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help.Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

June Gruber, Assistant Professor, Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Colorado Boulder and Jonathan Rottenberg, Professor of Psychology, University of South Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.