By Caroline Chen, ProPublica

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Pharmaceutical companies are racing to develop a coronavirus vaccine, with the most ambitious timelines ever attempted in history. When announcing Operation Warp Speed, the government's effort to develop a vaccine, President Donald Trump said in May, "We're looking to get it by the end of the year if we can, maybe before."

Vaccine development under normal circumstances typically takes about 10 to 15 years. Now, developers are compressing the traditional timeline with both technological innovation and by putting vast amounts of money at risk.

But one stage, the phase 3 clinical trial, which is the key to proving a vaccine's safety and efficacy, is frustratingly hard to predict in terms of its timeline. It's dependent on the rate of infection in the locations where the study is being conducted, because the goal is to compare how many people get sick in the vaccine arm of the trial versus the placebo arm. If public health measures, like social distancing, are working very well, and there are low rates of transmission, that's good for the general public, but it could take a long time for enough trial participants to get sick and for the study to come to a conclusion.

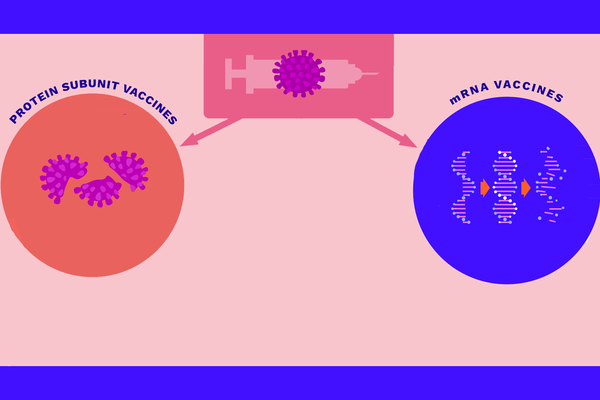

One potential shortcut to approval, if phase 3 trials are taking too long, is for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to authorize the use of a vaccine based on what's known as an "immune correlate." This was suggested by Dr. Philip Dormitzer, Pfizer's vice president and chief scientific officer for viral vaccines, and Dr. Tal Zaks, chief medical officer of Moderna Therapeutics. (Paul Sagan, chairman of ProPublica's board, is also one of Moderna's board members. ProPublica's board members have no say in what reporters write about, nor do they know about articles before they are published.)

The idea here would be to show that vaccinated participants have levels of neutralizing antibodies in their blood that are at least as high as patients naturally infected by the virus, and to greenlight the use of a vaccine based on its anticipated benefit, perhaps limited initially to some high-risk populations. Neutralizing antibodies are a type of antibody that can directly block a virus from infecting cells, but as of now, it's still unclear if there's a level of neutralizing antibodies that can guarantee immunity.

"We believe that by September there will be proof in animals that neutralizing antibodies can prevent disease, and that there will be proof that the vaccine, when given to people, can generate levels of neutralizing antibodies that are similar or higher than levels of antibodies in people who have been infected naturally, so some people will say that there is a reasonable likelihood that this should work, while people are continuing to die every day without a vaccine," Zaks said.

He added, "For any drug approval, there's always a balance between benefit and risk, so there's a rational question to be asked: In September or October, if I've demonstrated enough potential benefit, and I've made half a million doses, should the government start to vaccinate people who are exceptionally at risk, based on expected benefit, or should they wait for proven benefit?"

Some fear that this winter, as the annual flu season returns, there could be a "double threat" with both viruses circulating simultaneously, adding to the urgent need for a coronavirus vaccine.

Pfizer's Dormitzer said his company will be simultaneously running a full phase 3 trial while gathering data on antibody levels in vaccinated participants. "We want public health measures to reduce infection levels, but we also want a vaccine. That can create a dilemma if there aren't enough cases," he said. "We need a plan B, just in case."

Both Dormitzer and Zaks noted that ultimately, the decision is not for pharmaceutical companies to make but is up to the FDA. "It's our job to come up with the data and the arguments, and they say yes or no," Dormitzer said.

Other experts cautioned against approving a vaccine based on a proxy.

"There are still a lot of coronavirus cases in the United States. Given the current attack rate" — the pace at which people are getting infected — "you should be able to do a good study," said Dr. Luciana Borio, former FDA acting chief scientist and current vice president at In-Q-Tel, a nonprofit strategic investment firm. "There's still significant uncertainty about what level of antibody response will be required to prevent disease."

There is precedent for the FDA approving products based on a biomarker that is supposed to correlate with real-world benefit before trials are completed to prove benefit on symptoms or outcome of the disease. The agency has typically made these calls in cases where the need is acutely high, such as when patients have no other treatments available. Vaccines have been approved based on immune correlates in the past, when the rate of natural infection is low, such as meningococcal vaccine.

Sometimes, the FDA's decisions have been controversial, such as in 2016, when the agency approved a drug for a rare form of muscular dystrophy based on data from a trial with just 12 boys. The study showed that the drug helped some patients make dystrophin, a protein that is critical to muscle function. But the trial didn't have a placebo arm and the company didn't prove that its drug helped the patients walk or breathe better. The drug, Exondys 51, is still on the market, and the company is years behind schedule on a requirement to confirm the drug's benefit in muscle function.

The history of drug development is also full of surprising disappointments, which often come in the final-stage trials. For example, an experimental drug that lowered bad cholesterol in hundreds of patients in mid-stage phase 2 trials didn't end up proving its ability to prevent heart attacks or strokes in thousands of participants in the big phase 3 study.

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the vaccine education center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, noted that many approved vaccines on the market today don't have a known immune correlate. "The immune response may or may not be predictive," he said. "The proof is in the pudding. The pudding is the big phase 3 trial."

The FDA is in a difficult position of having to weigh risk and benefit, when the stakes are high on both sides, explained Dr. Tim Persons, chief scientist at the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

"It's one thing to say, ‘I want to be fast,' but on the other hand, if you're fast and you're wrong or you miss some things, imagine how that fuels concerns about having any type of vaccine at all," he said.

On the other hand, "CDC has reported that 8 in 10 deaths from the coronavirus are seniors, which is a terrible thing, so perhaps we're willing to take more risk and not wait a decade for a vaccine."

Evaluating vaccine efficacy may include looking at evidence of immune responses, which would entail a "rigorous scientific process" to determine which biomarkers could predict protection, the FDA said in an emailed statement.

"Provided the incidence of COVID-19 remains high enough to conduct randomized, controlled clinical trials that directly evaluate protection against disease, such studies are likely to be the most efficient way to demonstrate the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines," the agency said.

No matter what happens, Moderna is committed to completing its phase 3 trial, Zaks said, even if the FDA allows its vaccine on the market based on antibody data before the trial is complete. That way, there will eventually be data from a placebo-controlled, randomized trial.

After phase 3 trials begin this summer, everyone in the vaccine world will be watching the infection rates at the trial sites, anxiously hoping that the trials will be able to come to a definitive conclusion.

"Certainly, one hopes that the phase 3 trials will be large enough that they will be able to measure actual clinical protection," said Dr. Walter Orenstein, associate director of Emory University's vaccine center. "On the other hand, if you have 1,000 people dying a day in the U.S., you might be willing to take a chance. It's a last resort."

Filed under:

- Health Care