Though women make up half the adult population, research into women's health is disproportionately low. Of the nearly $42 billion the National Institutes of Health (NIH) spends on medical research each year, only approximately $5 billion of that funding is directed specifically at women's health.

Unequal allocation of research dollars is not only a matter of gender equity, it is a missed economic opportunity, according to a recent report from Women's Health Access Matters (WHAM), a nonprofit organization focused on demonstrating the economic imperative of women's health research.

"I come to this issue as a business leader, and for me, these disparities don't match up with the power women have in the global marketplace," said Carolee Lee, founder and CEO of WHAM. "In the U.S., women are the majority of the population, nearly 50% of the workforce, control over 60% of all personal wealth, and are responsible for 85% of consumer spending. Women also make over 80% of healthcare decisions for their families."

The WHAM Report presents an analysis of current research funding that is specifically for women's health in Alzheimer's disease and Alzheimer's disease-related dementias (AD/ADRD). It also models the potential impact of increasing that funding. The analysis was conducted on behalf of WHAM by the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit research firm.

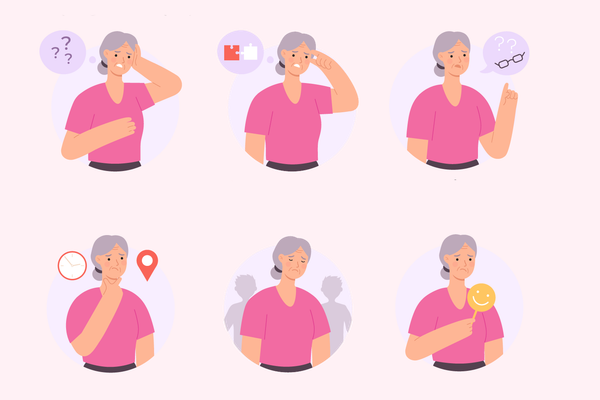

Of nearly 6 million people in the United States living with Alzheimer's disease, two-thirds are women. According to the report, only 12% of the $2.4 billion spent by the NIH on research into Alzheimer's disease is spent on research specifically focused on women.

The WHAM Report also found that spending more on research focused on women and AD/ADRD would yield significant financial results. Specifically, an increase of $300 million in research — approximately doubling the current NIH budget allocation — would result in $930 million of cost savings over 30 years. Those savings represent a 224% return on investment.

"Until now, to the best of our knowledge, no one has evaluated the economic consequences of the status quo, the costs we incur, and the benefits we leave on the table when women are underrepresented in research," Lee said.

The potential financial savings researchers identified are based on the assumption that targeted research would lead to improvements in rates and effects of AD/ADRD. For example, researchers assumed that research could delay the age of onset of AD/ADRD, slow the progression of the disease and improve health-related quality of life for people with AD/ADRD. Overall, researchers modestly assumed 0.01% health improvement.

But the impact of increased targeted research would be more than just financial. Researchers showed that quality of life, and life expectancy itself, would improve because fewer people would get AD/ADRD and those who do get the disease would have less severe symptoms.

Even a small 0.01% health improvement would save lives, lower the number of years people live with AD/ADRD and greatly reduce the number of years AD/ADRD patients spend in nursing homes.

Improving care for people with AD/ADRD — and fewer people getting AD/ADRD in the first place — would also benefit millions of unpaid caregivers, 60% of whom are women, according to a 2020 AARP report on family caregiving.

This is significant because caregivers often sacrifice their own health and economic well-being for loved ones with AD/ADRD. The report showed that 21% of caregivers rate their own health as fair or poor, which is worse than the national average. Nearly one-quarter (23%) of respondents in the 2020 survey said it was difficult to care for their own health while caregiving, and 38% characterized caregiving as stressful.

In addition to health and mental health burdens, caregivers also pay a financial price. Increased research funding could ease the economic burdens for women in caregiving roles. Women caregivers, especially those caring for people with Alzheimer's disease, are often pulled out of the workforce in their prime, according to Meryl Comer, a co-founder of UsAgainstAlzheimer's and chair of the Global Alliance on Women's Brain Health.

"What does it do to your health in caring for a loved one?" Comer said. "It makes you the invisible patient. To me, this makes a very important economic statement: Don't forget the caregiver."

The WHAM Report estimates that even modest health improvements from increased AD/ADRD research would save caregivers 800 years of lost productivity.

Alzheimer's disease is by no means the only area where increased research funding could improve health outcomes, and WHAM plans to release additional studies in the fall on the impact of autoimmune and cardiovascular disease research funding on health outcomes. But Alzheimer's disease is a good case study to start with, according to Comer.

"It falls into one of the buckets where women are impacted differently and differentially," she said. "With a small investment in the Alzheimer's space, the payoffs are big."

Comer sees the WHAM Report as an opportunity to change the conversation about women's health research. By focusing on economic arguments, she hopes the data will help advocacy groups and researchers increase the effectiveness and urgency of the case for increased funding.

"If we don't make a stand now, when?" Comer said.