Reviewed by Maria Elena Bottazzi, Ph.D.

Developed in record time, the first COVID-19 vaccine was authorized for use in the United States on December 11, 2020. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine that day, followed by an EUA for Moderna's vaccine a week later.

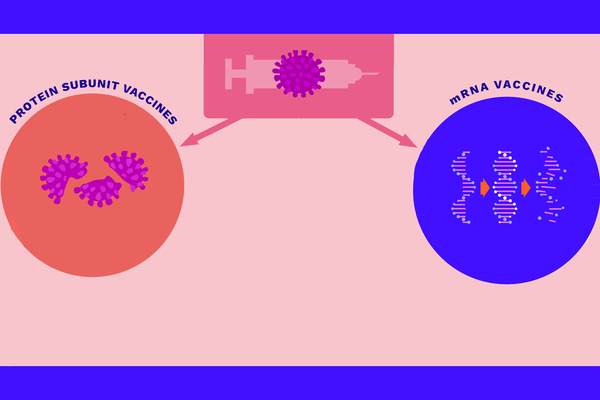

Nine months of clinical trials have shown that the vaccines, which make use of messenger RNA (mRNA), a molecule that holds instructions for making proteins, are both safe and effective. While clinical trials typically take years, scientists and regulators worked to speed up the vaccine development process while preserving the same high standards for safety.

Several COVID-19 vaccines have now been developed four times faster than the previous record-holder, the mumps vaccine. Science, funding and the urgency of a new, widespread virus allowed the COVID-19 vaccine to be created safely in a condensed time frame. Lessons learned from this process could improve vaccine development in the future.

A head start

The COVID-19 vaccines weren't created from scratch. Scientists have worked on coronavirus vaccines for years, starting with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) vaccine in 2003 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012. However, work on those vaccines slowed when the SARS and MERS pandemics ended and funding subsequently sputtered out. So, when COVID-19 emerged, scientists could draw upon years of relevant research.

This research gave scientists a potential vaccine target, the spike protein. Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease COVID-19, infects cells via that protein. Well before 2020, virologists had developed ways to modify the spike protein during SARS and MERS vaccine research.

Scientists also drew upon important advances in vaccine development. Developers had been working on mRNA vaccine platforms for several years before 2020 to combat a number of viruses. For example, an mRNA vaccine for rabies underwent an early-stage clinical trial from 2013 to 2016 and proved safe for human participants.

No mRNA vaccine has been licensed before now, but that's due to a number of reasons unrelated to safety. First, to move a vaccine from research to production, funding is required. Further, to test a vaccine, the target virus needs to be circulating in the testing population. In the case of Zika, for example, spread of the virus significantly decreased before the completion of vaccine trials, and funding the vaccine was no longer a priority.

Vaccines based on mRNA have the advantage of speed. In traditional vaccine production methods, it can take months to grow modified, weakened viruses, pieces of which are used in vaccines like the flu shot. Advances in genetic engineering have led to the new mRNA approach, where scientists engineer certain viral genes to be used in the vaccine. For this approach, scientists only need the virus's genetic information, not the actual virus.

With a lot of basic science to draw upon, scientists were able to get a quick start when the SARS-CoV-2 genome, the complete set of the virus's genes, was published on January 10, 2020.

Safely redefining the process

A well-funded and streamlined development process also helped deliver a vaccine in under a year. Unlike other vaccines, COVID-19 initiatives benefited from readily available funding from governments and philanthropists, widespread scientific collaboration, and the political will to fill an urgent, global need. SARS-CoV-2 is also an easier vaccination target compared to other pathogens, due to scientists' knowledge of coronaviruses.

In clinical research, regulatory steps and funding are two major factors that determine how long it takes a vaccine to get FDA approval. Outside of pandemics, waiting for companies to invest in various stages of vaccine development is a slow process. Funders want to know that vaccine candidates are successful before they invest, but the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic overcame that need. Money not only speeds up vaccine development but also ensures companies have enough funding to manufacture vaccines for the public.

In the U.S., Congress directed nearly $10 billion in funds to Operation Warp Speed, the initiative to produce and deliver 300 million doses of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines. Operation Warp Speed gave over $1 billion each to AstraZeneca, Novavax and Moderna, among others, to support development of their promising vaccine candidates. These amounts tower over funds for development of past vaccines. Operation Warp Speed also provided funds for manufacturing potential vaccines.

Similar government funding initiatives around the world, like the European Commission's vaccine program and the U.K.'s Vaccines Taskforce, have taken similar steps in their respective regions.

There were other ways to speed up development while maintaining stringent safety requirements and without skipping steps. With the large amounts of funding, vaccine developers saved time by conducting some steps in parallel. They could plan the three phases of the clinical trials all at once, and, once safety was established in the earliest phase, they could conduct phase 2 and phase 3 trials simultaneously. This normally doesn't happen due to the financial risks of sinking money into wide-scale testing of a product that might fail.

COVID-19 vaccine trials also differed from prior vaccine trials in the number of participants willing to test the vaccine right away. Public interest to be of service to the nation during an emergency meant there was no shortage of volunteers. Tens of thousands volunteered for vaccine trials in a few months, when past clinical trials have taken over a year to recruit just a few thousand participants.

With ample funds and regulatory support, scientists had the resources to conduct their work with their usual safety protocols in place, but faster. Vaccinations in the U.S. began in December, and millions have been safely vaccinated. For the vast majority of people, the risk of rare allergic reactions, which can be treated, is worth the benefits of protection from COVID-19.

The risks posed by COVID-19 are much higher. According to Johns Hopkins' Coronavirus Resource Center, in the U.S., for every 100 confirmed COVID-19 cases, between one and two people die. An even larger proportion develop long-term symptoms.

A new model

Current gold standards and protocols for vaccine development are important to preserving trust in science, and scientific advancements that made COVID-19 vaccines possible may be applied to future trials. The protocols used during the pandemic should be carefully reviewed and, where possible, adopted by future clinical trials.

Updating protocols and keeping up with scientific modernization are critical to our ability to address illnesses and diseases that are spreading worldwide. For so long, clinical trial research has taken years to get medicine on the market. Now is the time for consideration and transformation of scientific research. By consolidating steps in clinical trials, time and money can be saved while still enabling new treatments, therapies and devices to reach people who need them.

This resource was created with support from Merck.