As Krystal Allan watched Alzheimer’s disease ripple through her family, her own outlook on life changed.

“On my dad’s side, several relatives including my grandmother had Alzheimer’s,” said Allan, an award-winning anchor with News 3 Las Vegas. “I saw firsthand what it was like — for the patient and the caregivers.”

That family history led to a sense of inevitability about her own future.

“When your loved ones decline and your family members become caretakers, there’s a nagging fear that ‘this is probably going to happen to me,’” Allan said.

Watching someone you love suffer from Alzheimer’s is watching them fade away, piece by piece. After living through that devastating experience, Allan began preventive treatment at the Women's Alzheimer's Movement (WAM) Prevention Center at Cleveland Clinic. At first, her main focus was educating others more than anything else. But what she learned shifted her entire perspective. “I was shocked to find out that 40% of [Alzheimer’s] cases could be delayed or avoided altogether by making healthy lifestyle changes early on,” Allan said. “It has been such a positive shift to learn that my family history doesn't necessarily determine the trajectory of my brain health.”

Fighting the devastation of Alzheimer’s disease

Teaching women that they can take steps to prevent Alzheimer’s, currently the seventh leading cause of death in the country, is the core message at WAM, where the goal is to help women reduce their risk. “Family history is hugely important, as it tells us a lot about the risk, and motivates many women to seek preventive care,” said Jessica Caldwell, Ph.D., director of the WAM Prevention Center at Cleveland Clinic. “Our work is increasing what we know about women who are most at risk, who are seeking preventive care and the factors putting them at risk. This is the kind of data leading us forward to develop more effective treatments and preventive care protocols.”

It can’t come a moment too soon.

In the United States, about one in 10 people over the age of 65 have Alzheimer’s. And almost two out of three of those people are women. While we don’t know all of the factors that put women at higher risk, research shows that menopause and the corresponding drop in estrogen lead to decreased activity and energy in the brain. Sex-specific differences in certain genes and in connections between regions of the brain may also contribute to increased risk for women.

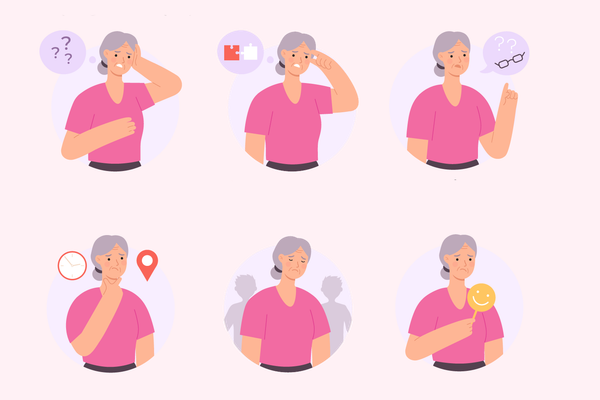

Forgetfulness vs. dementia

Everyone knows what it’s like to go blank on a piece of information, like where you left your keys, or why you just walked into a room. Forgetfulness is part of everyday life. As we age, it’s normal for those moments of forgetfulness to increase.

Dementia, however, is different from these moments of forgetfulness.

“Forgetting where you left the keys is a normal moment. Forgetting what keys are is something else,” said Heather Snyder, Ph.D., vice president of medical and scientific relations for the Alzheimer’s Association. “Dementia is an umbrella term for changes in memory, thinking and reasoning that impact our everyday functioning and ability to to be independent.”

Stopping Alzheimer’s before it starts

Some of the major risk factors for Alzheimer’s — such as age, genetics and family history — are not controllable. But other factors that people can control have become a focus in Alzheimer’s prevention.

WAM uses evidence-based preventive care and gathers clinical data to learn how prevention strategies can improve. “We work with women to help improve the risk factors they can [improve],” Caldwell explained. “For example, there are avoidable risk factors, like diabetes, and we can make changes to diminish their effect. Others are controllable lifestyle factors that can have a major impact, like smoking, drinking, nutrition, mood, stress and sleep.”

This type of preventive research and clinical trials are a big part of helping us understand how controlling these factors can help prevent Alzheimer’s.

“There are all different kinds of trials, and they are such an important aspect of moving forward,” Snyder said. “There are drug trials as well as trials testing biomarkers, looking at new measures of the underlying biology and dealing with care interventions, risk reduction and behavioral interventions.”

One of the major trials, led by the Alzheimer's Association, is a lifestyle intervention trial known as U.S. POINTER. This trial is part of a global network expanding on the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER) clinical trial, which showed that lifestyle interventions — such as diet, exercise and cognitive training — can help preserve cognitive functions. It’s the first of its kind in the U.S. and is still open for participants.

The Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP), run by the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, is one of the longest-running and largest studies on Alzheimer’s in the world. By building a registry of volunteers, WRAP has been able to build a comprehensive data set tracking lifestyle, fitness, biomarkers, genetics and more to understand what, and how, these factors affect Alzheimer’s risk. While still ongoing (and open for new participants), the study has found that certain biomarkers are associated with cognitive decline, while healthier lifestyle choices are linked to better cognition and brain structure.

Currently, the National Institute for Aging (NIA) is supporting over 400 active trials on Alzheimer’s and dementia. While some are drug trials, the majority are not. There are 139 trials focused on intervention modalities like exercise, cognitive training, sleep and diet.

Finding hope beyond limited treatments

The most promising research is focused on earlier diagnosis and preventive measures to help slow — and perhaps stop — the progression of Alzheimer’s disease even before plaque buildup forms. For women in particular, it’s key to identify the underlying factors as early as possible. “If we can provide people with a longer period of prevention and treatment when they're in the early stages, that's beneficial for them,” Snyder said.

One brain imaging research study at the Weill Cornell Women’s Brain Initiative (WBI) is examining the connection between declining estrogen and increased Alzheimer’s risk in women. Other current research is pinpointing specific approaches to prevention, which can then be translated into clinical trials. For example, recent studies indicate that taking a daily multivitamin, lowering blood pressure, getting timely treatment for depression, staying physically fit and improving sleep habits all play a part. If that seems like a lot, take heart: One recent study on diet modifications found that red wine and cheese help protect cognitive functions.

Prevention and early diagnosis are important because there’s no consensus on a single cause for Alzheimer’s. It’s most likely that a variety of complex interactions is to blame. Without a clear cause, treatment is very limited for the 6 million people living with the disease. “There are medications that treat the symptoms but do not prevent the progress of the disease itself, so eventually even those medications aren’t helpful anymore,” Caldwell said. “The only medications that attack a base cause are very new and not really accessible yet. While they may offer help in reducing or eliminating some of the plaque buildup, they’re also still quite limited.”

Getting involved for a healthier future

The more clinical trials we have — and the more diverse the participants — the better. As more women get involved, there’s real hope of making preventive care available and effective for anyone at risk.

Getting started is as simple as finding a trial that’s locally available and checking the qualifications. The Alzheimer’s Association offers a service called TrialMatch to help people find and participate in clinical trials. The NIA and Mayo Clinic offer other tools for finding clinical trials. Major research centers, universities and hospitals involved in Alzheimer’s research typically offer a list of open studies as well.

The real first step is making a decision to get involved. “When you’re on a plane, they always say put on your mask first before you help someone else. I look at this as putting on my oxygen mask,” Allan said. “I'm taking care of myself first, because I know if I'm better, then the people around me are going to be better, too. This is something that affects all of us.”

- Alzheimer's Disease Hub - HealthyWomen ›

- What's the Link Between Menopause and Alzheimer's? I Set Out for ... ›

- You & Your Brain: A Collaboration of HealthyWomen, Prevention & Women’s Alzheimer’s Movement at Cleveland Clinic ›

- Important Questions to Ask About Alzheimer’s Disease ›

- 7 Easy Ways to Prevent Alzheimer's - HealthyWomen ›

- Treatment Options for Alzheimer’s Disease - HealthyWomen ›